The story of Magdalen’s servants and staff in its first centuries is one of contradictions. Although a key part of college life, and employed in significant numbers, the majority have left little to no trace in the historical record. The story of Magdalen’s early staff is also one of unusual terms and arrangements, wherein lines were both rigidly fixed and occasionally blurred between those on the college’s ‘foundation’ (e.g., its Fellows) and those who were not.

No figure quite so epitomised these elastic circumstances as the ‘servitor-scholar’/‘poor scholar’, who supported their studies at Magdalen in the fifteenth to seventeenth centuries by carrying out domestic tasks for the President, Fellows, or those wealthier students who employed them. Admitted in large numbers, their role was ‘servile’ in one sense, but their place in the college hierarchy shows it would be anachronistic to assume hard and fast distinctions between academic persons and every ‘servant’ at this point in Magdalen’s past.

Moreover, not every person directly employed by Magdalen in its early years worked in a menial capacity. Senior administrative positions were sometimes filled by a Magdalen-educated man who might occupy his charge for much longer than the average Fellow. Lower-ranking posts (porter, butler, cook, etc.) could also be occupied by the same person for many decades, meaning that it was the staff, rather than the Fellows and students, who provided continuity at college across the decades. Wages could certainly be poor, but bare figures often obscure the earning potential, perks, and prestige of some college posts.

The business of keeping Magdalen running also brought to it a steady stream of casual labourers, including women, whose presence was otherwise strictly forbidden. Initially meant to serve exclusively as laundresses, and only then under certain conditions, records from the archives show them performing other tasks, such as the cleaning of the college library (now known as the ‘Old Library’), which was carried out by one Mrs Dunclett and her sons in 1628.

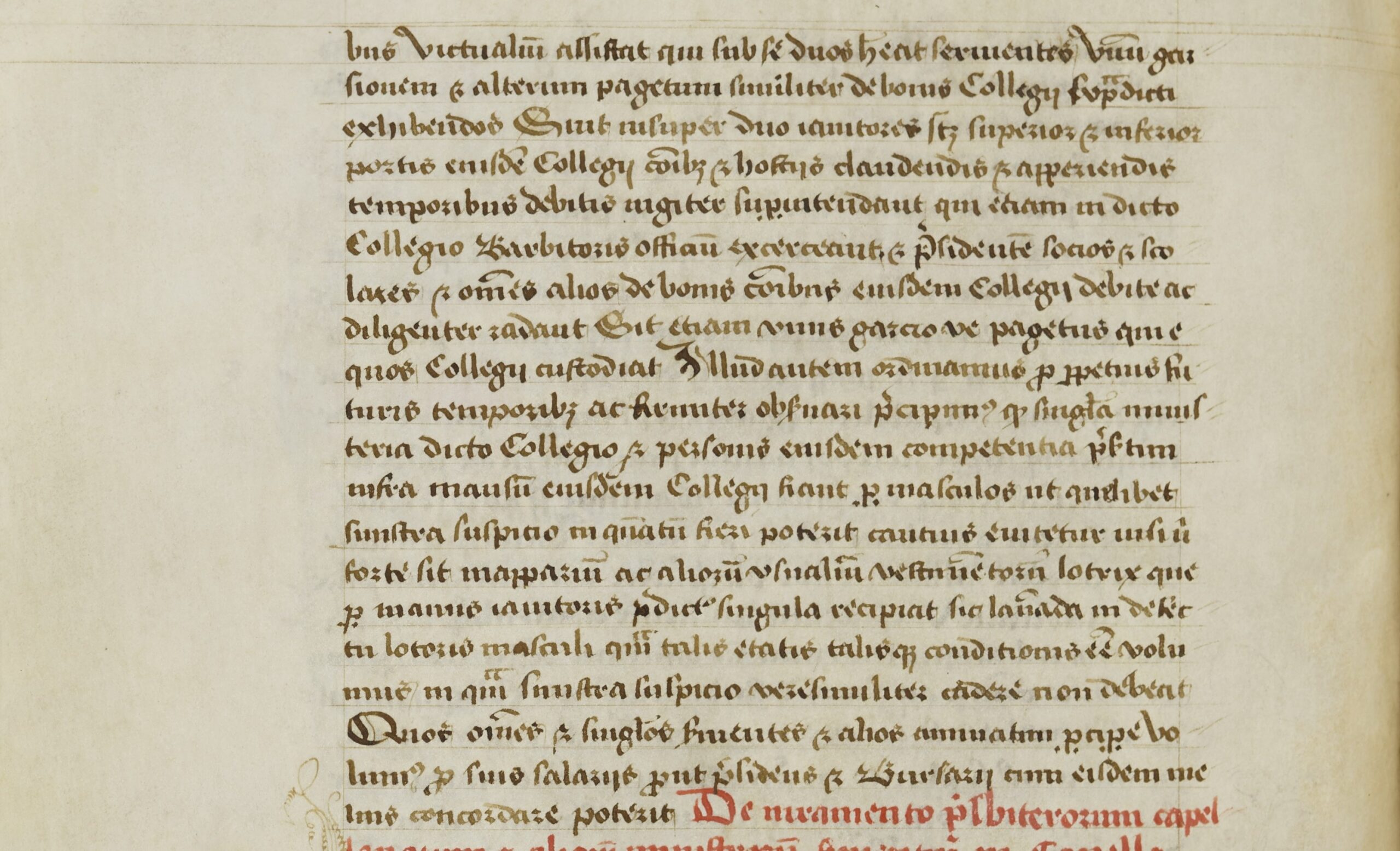

Original Magdalen College statutes, 1480

Clause stipulating that women may act as laundresses only if they are of an age and condition ("quam talis etatis talisque conditionis") not to bring suspicion on the college.

College statutes

These are the original college statutes, as written by Magdalen’s founder, William Waynflete (c.1395–1486). They cover the workings of every aspect of college life, including the employment of servants. This particular clause stipulates the posts that are to be created and the sort of people who should occupy them. Provision is therefore made for a cook, manciple, and porters, all of whom must be men. Women are only to act as laundresses, and only then if ‘they are of an age and condition’ (quam talis etatis talisque conditionis) so as not to bring suspicion upon the college.

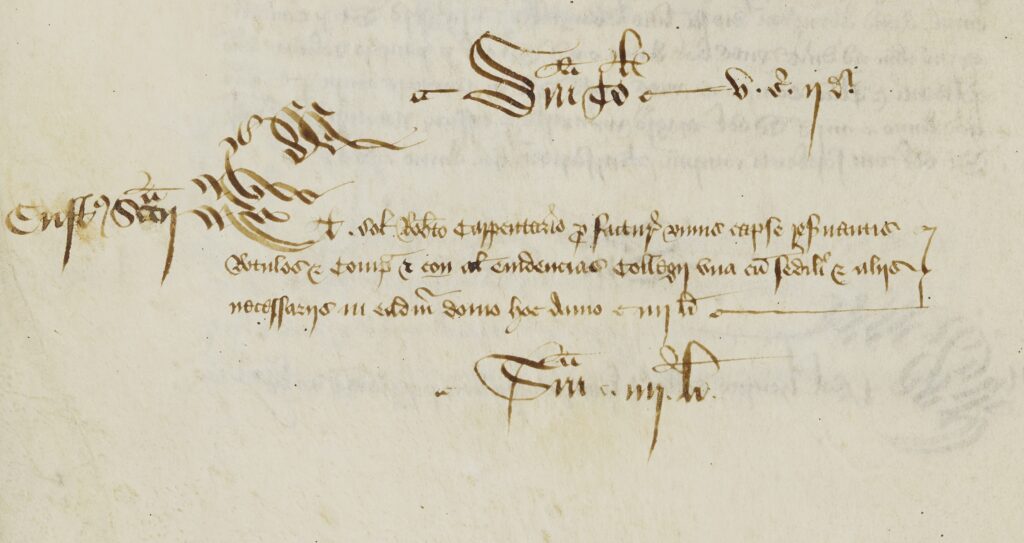

MCA, MS/278

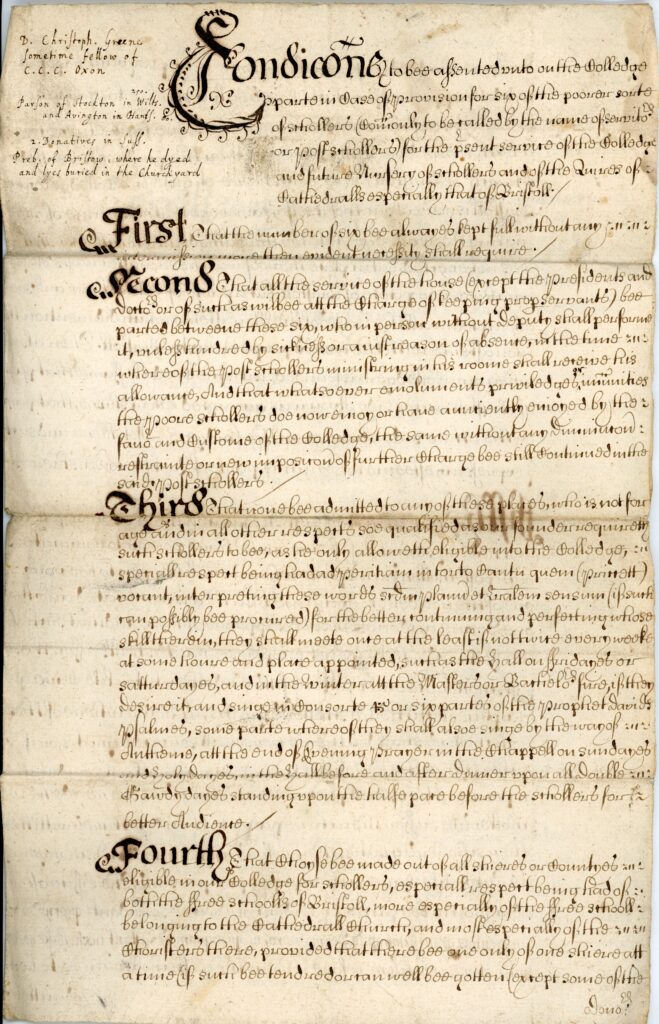

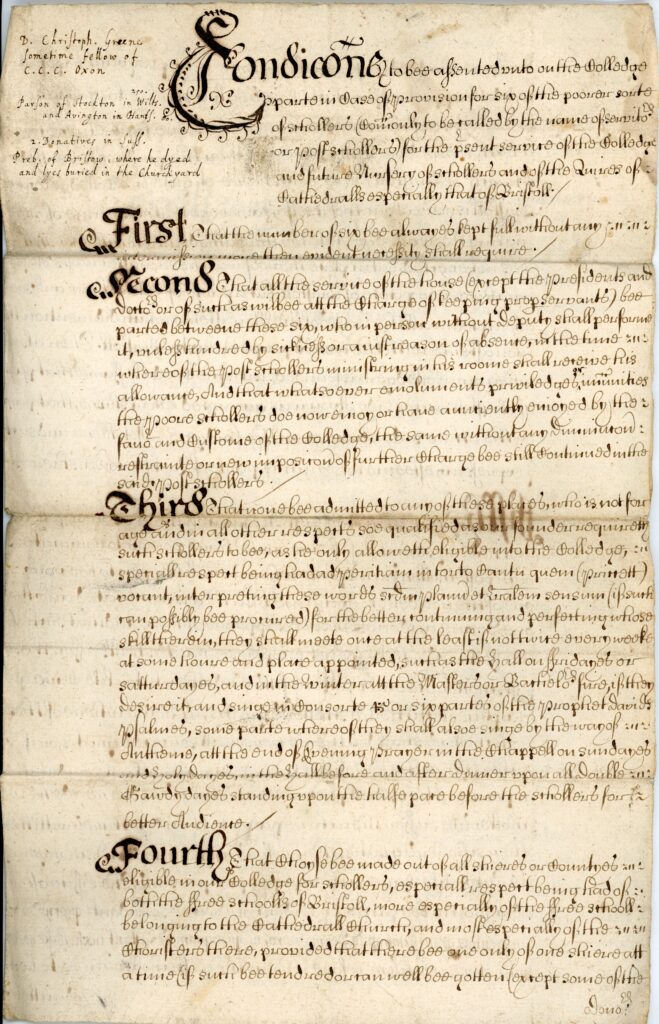

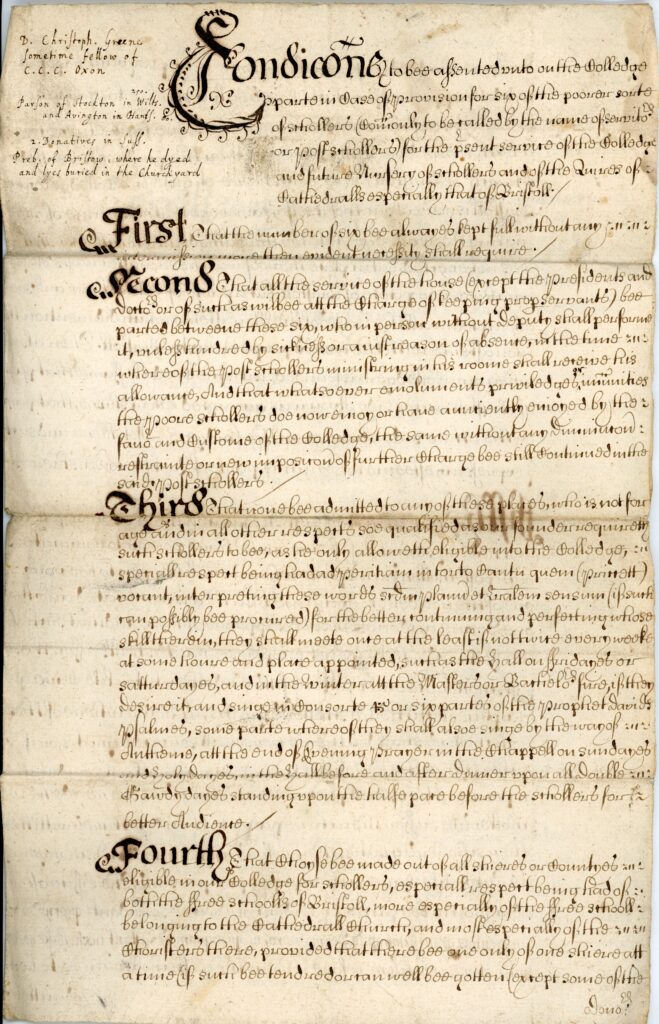

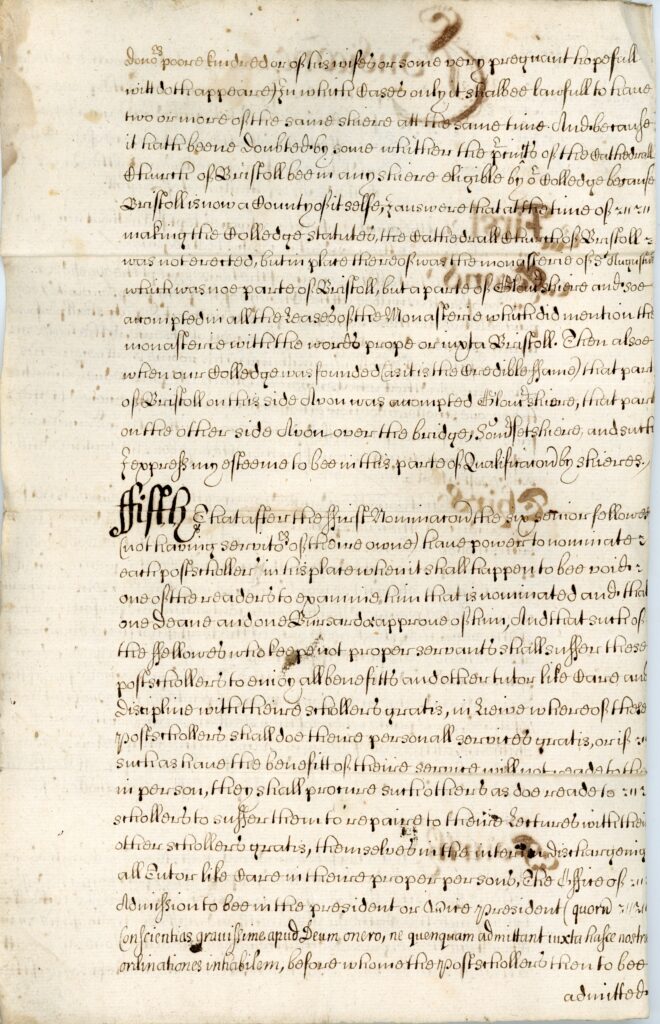

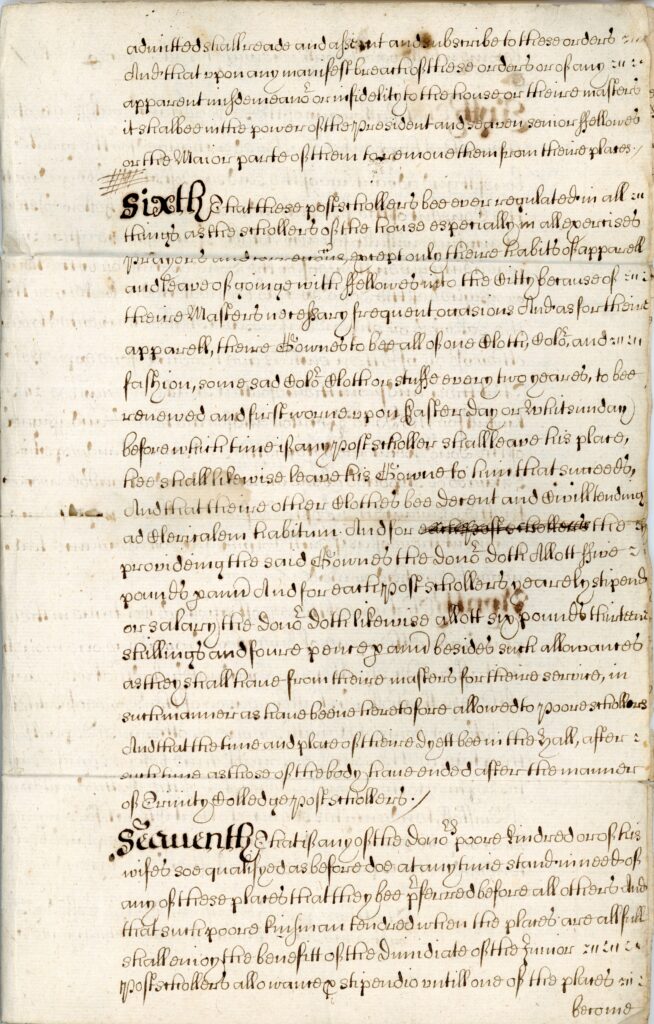

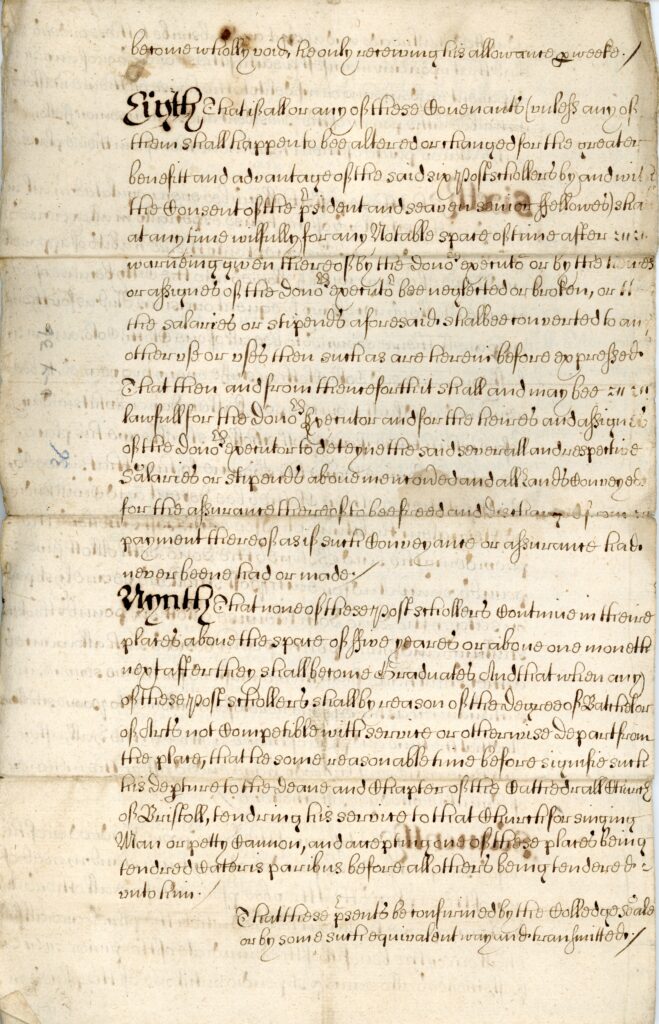

Servitor-scholars

‘Servitor-scholars’ were poor students who subsidised their studies at Magdalen by performing domestic tasks for other college members, including Fellows. We know they were here in large numbers, but the sources refer to them most often collectively rather than by name.

This text sets out the terms relating to the provision of six servitors. The document’s origins are unknown, since it is one of hundreds extracted from the college’s estate papers without provenance notes by Noël Denholm-Young (F 1931–46). It is possible, in fact, that it relates to Corpus Christi College, given the mention of a former Fellow of that college in the top left-hand corner.

Whether it concerns Magdalen or not, this text gives a useful insight into the conditions under which servitor-scholars might be present at Oxford, including regulations on dress. In this example, they are required to dress identically, in gowns of a ‘sad’ (sober) colour.

MCA, EP/ER/WL/MNH/M/1

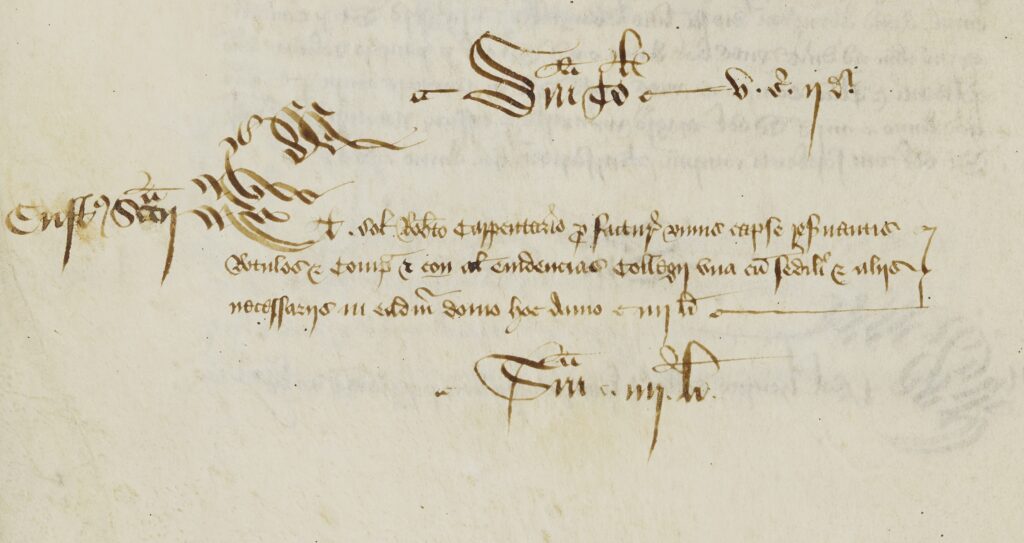

Carpenter by name

Not all those who worked for Magdalen in its early years did so as direct employees. Carpenters, masons, and other specialised tradesmen would have been a regular sight at college throughout the fifteenth to eighteenth centuries, much as they are today.

The account book extract above contains evidence of one such individual being remunerated by the college for specialised work. Named Robert Carpenter, he was paid £4 in 1483 for the making of a casket (capsa) for the storing of rolls, accounts, and other ‘college evidences’ (evidencias collegii).

MCA, LCE/1(iv), fol. 76v

Deed box

This is one of nearly 140 medieval wooden boxes in which Magdalen’s collection of over 13,000 medieval deeds are still kept. Containing documents relating to land and property at Wootton, Oxfordshire, it is today housed in the college’s purpose-built fifteenth-century muniment room. It is much smaller than Robert Carpenter’s casket would have been, but is stored in the same space where his likely still lives.

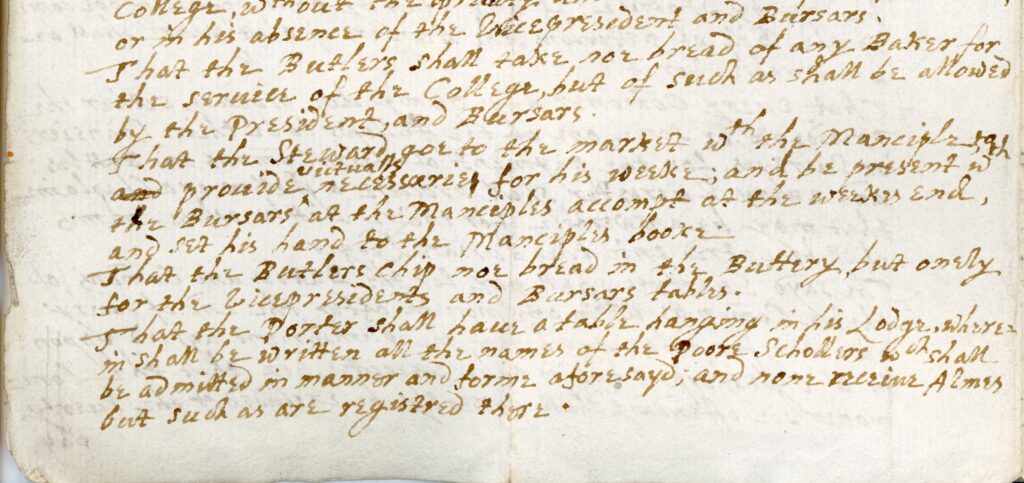

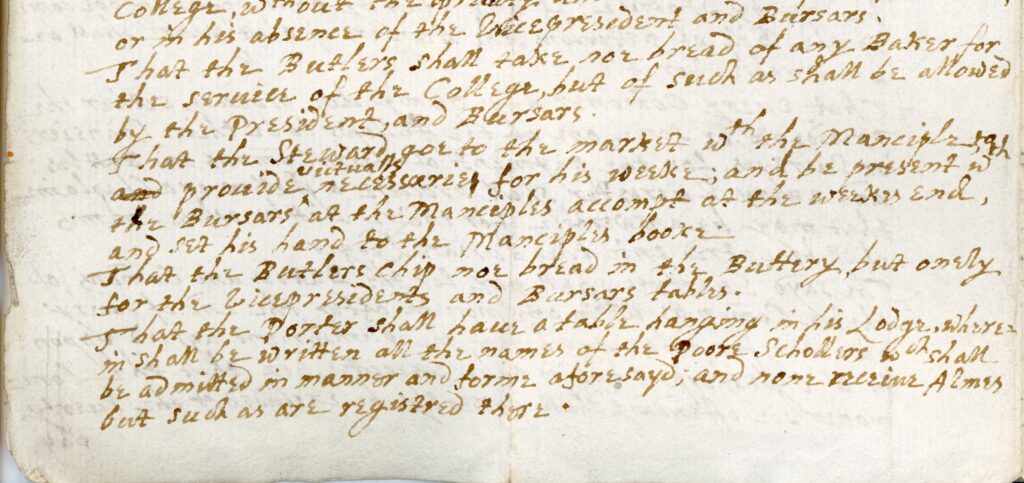

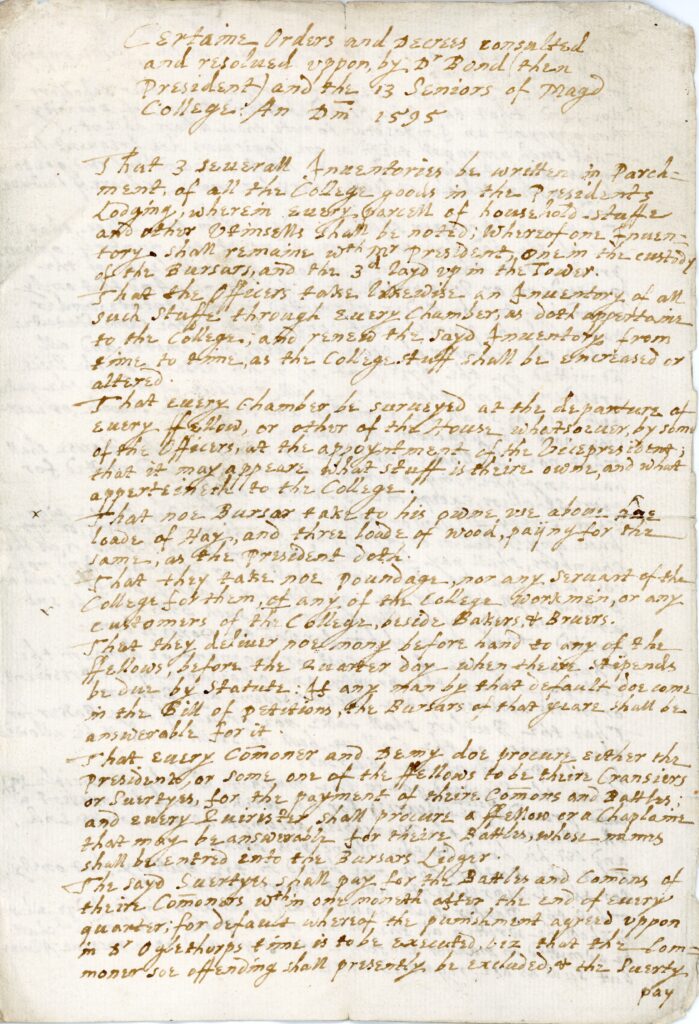

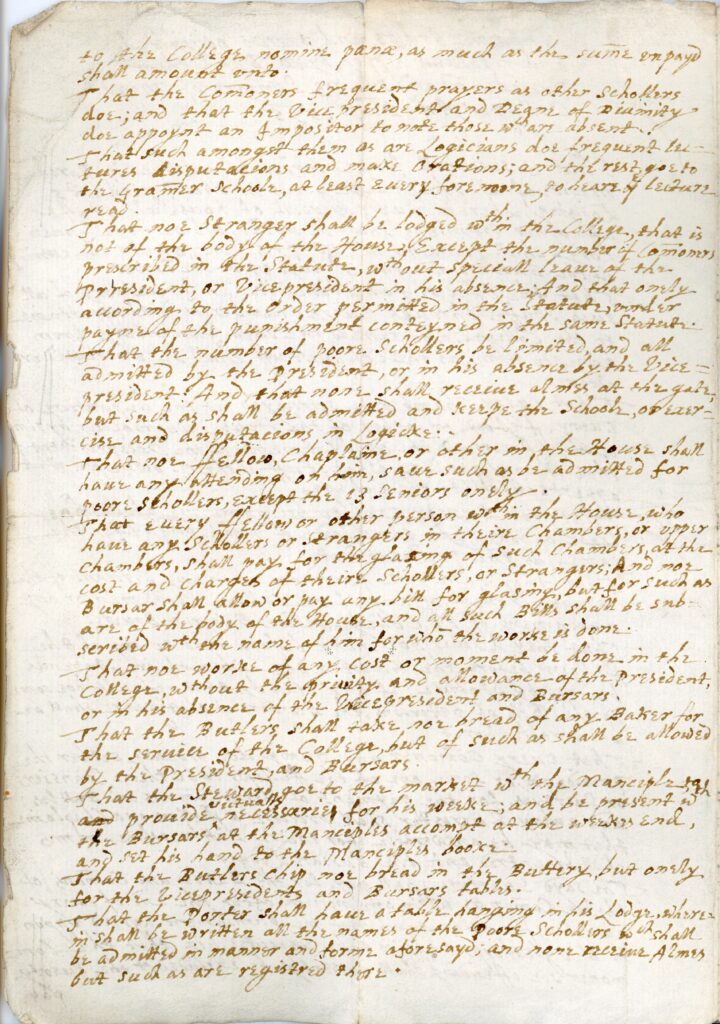

Rules and regulations

Besides the statutes, which codified the principles on which the college was to be run, additional orders and decrees were sometimes issued at early modern Magdalen, governing anything from the inventorying of moveable goods, to the payment of college charges (‘batells’), to attendance at prayers in the chapel. This document was drawn up in 1595 by Magdalen’s governing body, which consisted of the President, Nicholas Bond (1590–1608), and the 13 most senior Fellows.

The manciple, whose job was to procure weekly provisions for the college, is hereby instructed to make his visits to market in company with the steward, whose role was to oversee Magdalen’s accounts alongside the three bursars and to administer the college’s estates. The steward is directed to present himself at the weekly view of the manciple’s account book and set his signature thereto.

A table of all the poor scholars is ordered to be hung in the lodge, and the porter is enjoined to refuse entry and alms to anyone not listed there. When serving bread in the buttery, the butler is directed not to remove the crusts (‘chip’ the bread) for anyone but the occupants of the Bursar’s and Vice-President’s tables.

MCA, De situ collegii 24

Elizabethan Magdalen

This is the earliest known depiction of Magdalen, drawn by John Bereblock for a visit of Elizabeth I in 1566.

Bodleian, MS. Bodl. 13, part I, fol. 8v. © Bodleian Libraries, University of Oxford.

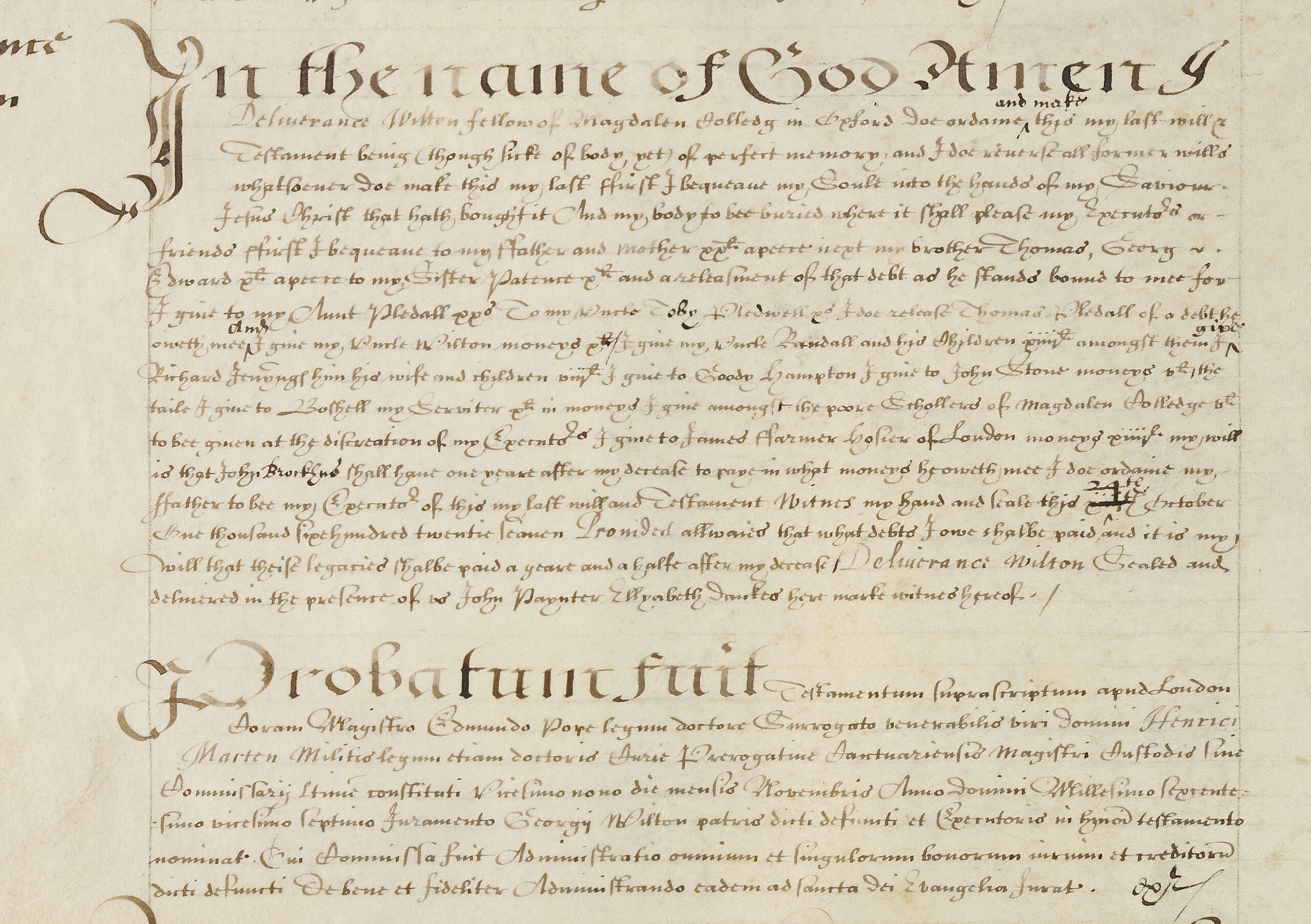

Will of Deliverance Wilton, Fellow of Magdalen

Wilton bequeaths £10 to his servitor, 'Bothell'

Will

Servitor-scholars rarely appear – if at all – by name in the college archives. This will contains a rare personal mention of a Magdalen servitor. Proved in 1627, it leaves £10 to a certain ‘Bothell’, who was servitor to a Fellow called Deliverance Wilton. The will further stipulates that, once received, the money be distributed amongst Magdalen’s ‘poor schollers’.

TNA, PROB 11/152/755. © The National Archives. Reproduced with permission.

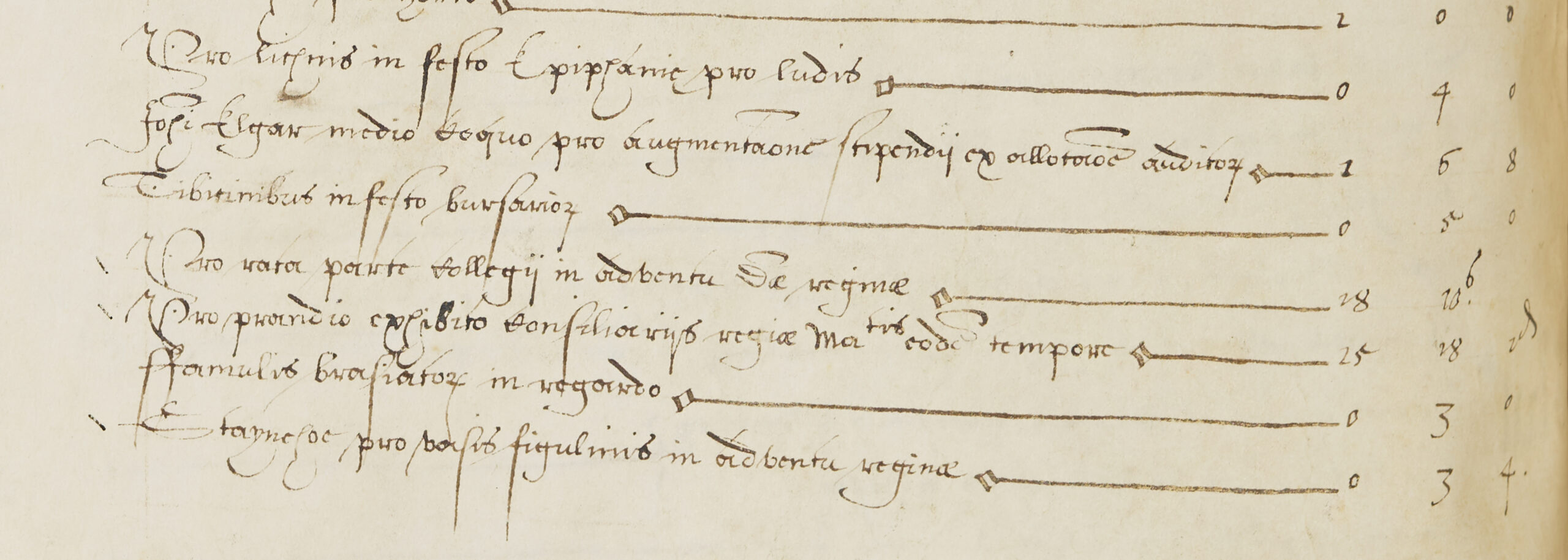

Payment to 'Stayno'

This entry from the account book for 1592 shows that one 'Stayno' was paid 3s 4d to make pottery jars ("vasis figulinis") for Queen Elizabeth I's visit to Magdalen College.

A royal visit

Although servant wages could be poor at early modern Magdalen, there were opportunities for those employed by the college to supplement their income.

The account book extract above shows ‘Stayno’, the college’s long-serving head cook, being paid 3s 4d to make pottery jars (pro vasis figulinis) for the visit in 1592 of Elizabeth I. Other accounts show him caring for the kitchen garden and the college’s dishes, with such work helping to more than double his formal income of £2.

MCA, LCE/7

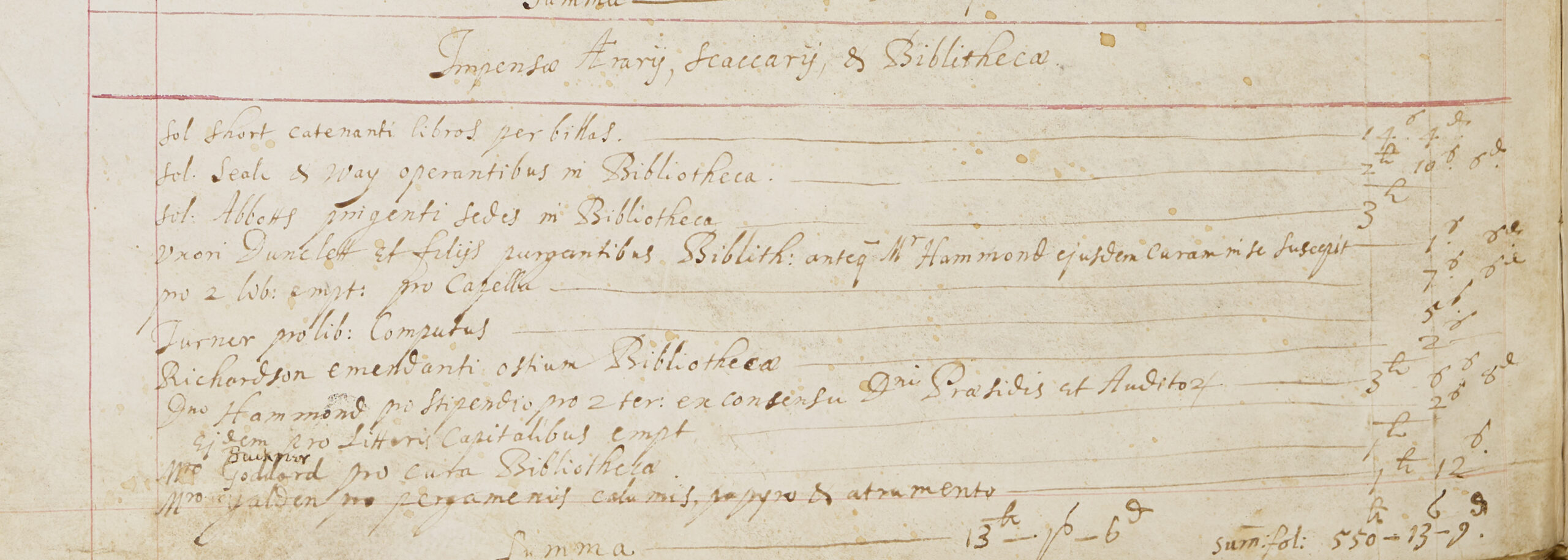

Mrs Dunclett and sons clean the library

This record shows that Mrs Dunclett and her sons were paid 1s 6d in 1628 to clean the Magdalen College library

A woman’s work

The college statutes strictly regulated the presence of women within Magdalen’s walls, ostensibly allowing them access under only certain narrow conditions.

Magdalen’s account books, however, reveal such rules were not always strictly adhered to. The above entry from 1628 shows one Mrs Dunclett and her sons being paid 1s 6d to clean the library (known today as the ‘Old Library’). Mrs Dunclett was likely the wife of William Dunclett, who served the college for more than 50 years in its stables.

MCA, LCE/15

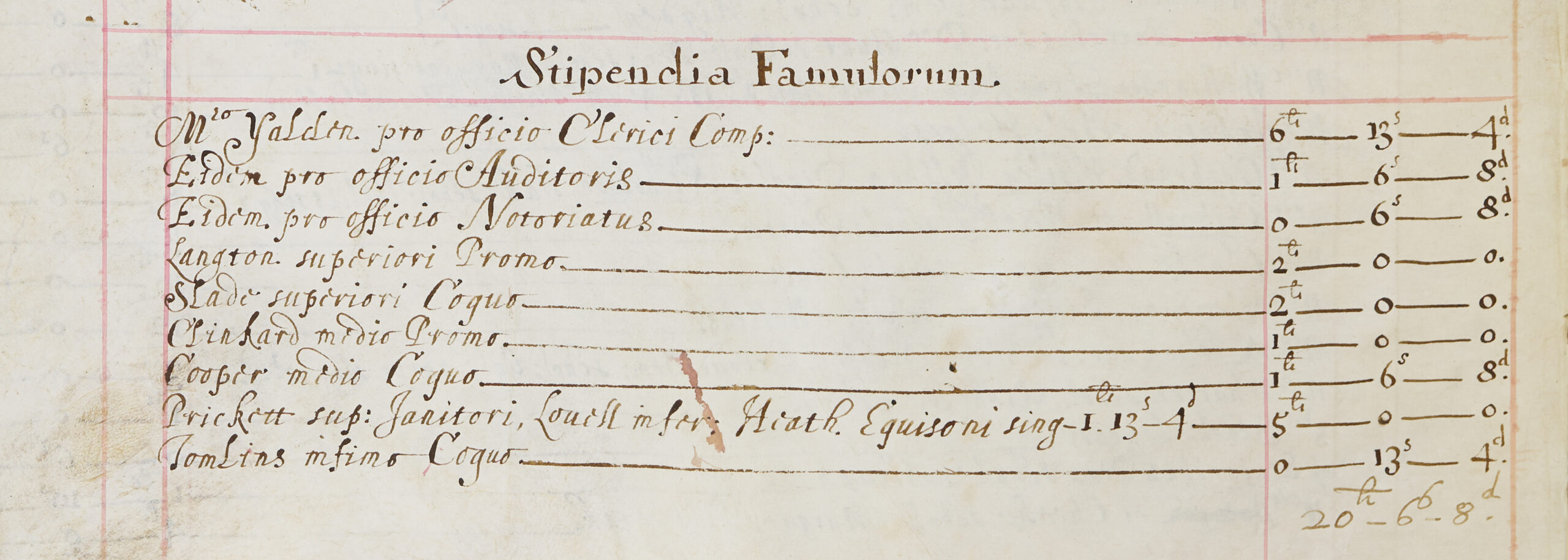

Pricket the head porter

This record in a 1630s account book details a payment to 'Pricket', who was head porter at Magdalen College from 1633/4 to 1670/1

Long service

At medieval and early modern Magdalen, the average Fellow might be at college for no more than ten years. Students were here for even shorter periods. It was therefore the servants who most often provided continuity across the decades.

The account book entry shown above relates to a certain ‘Pricket’, who served as head porter between 1633/4 and 1670/1. Doubtless known to hundreds of Magdalen men, we know nothing of Pricket save his last name.

MCA, LCE/22

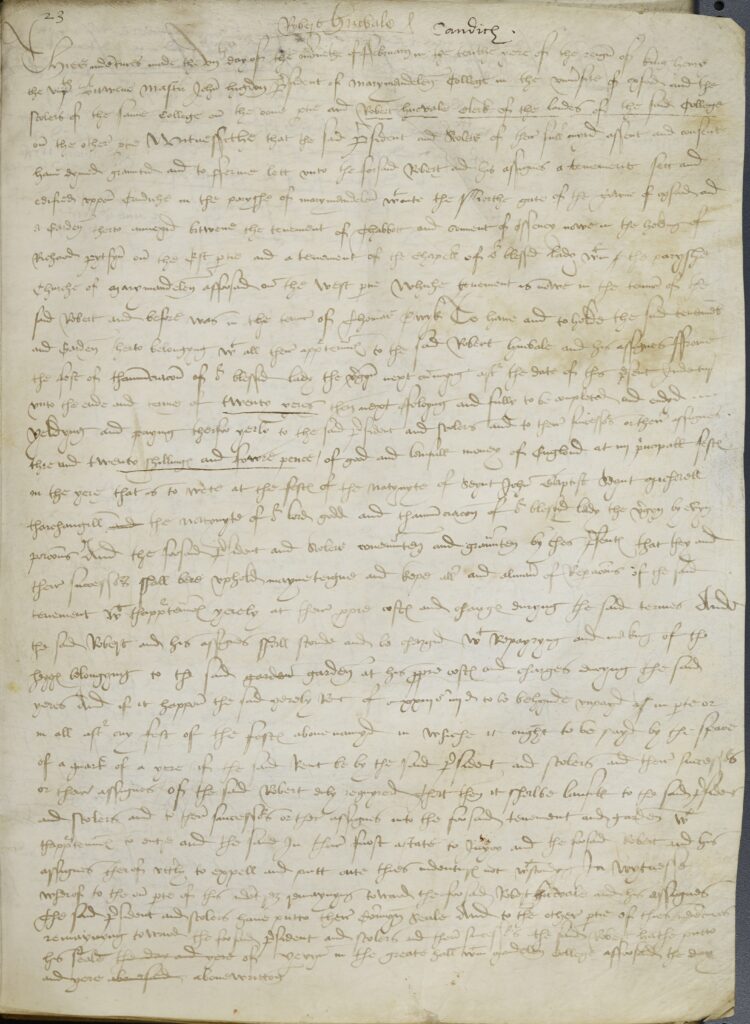

Lease

Servants at early Magdalen might sometimes find the college acting as both employer and landlord.

By this document, dated 7 February 1518/19, the President and Fellows lease for twenty years to one Robert Huckvale, who was then clerk of the college’s lands, a tenement and garden in Canditch in the parish of St Mary Magdalen outside Oxford’s north gate.

Huckvale’s post was an important one, and the length of the lease suggests either he or the college expected him to work at Magdalen for many years.

MCA, EL/2/16

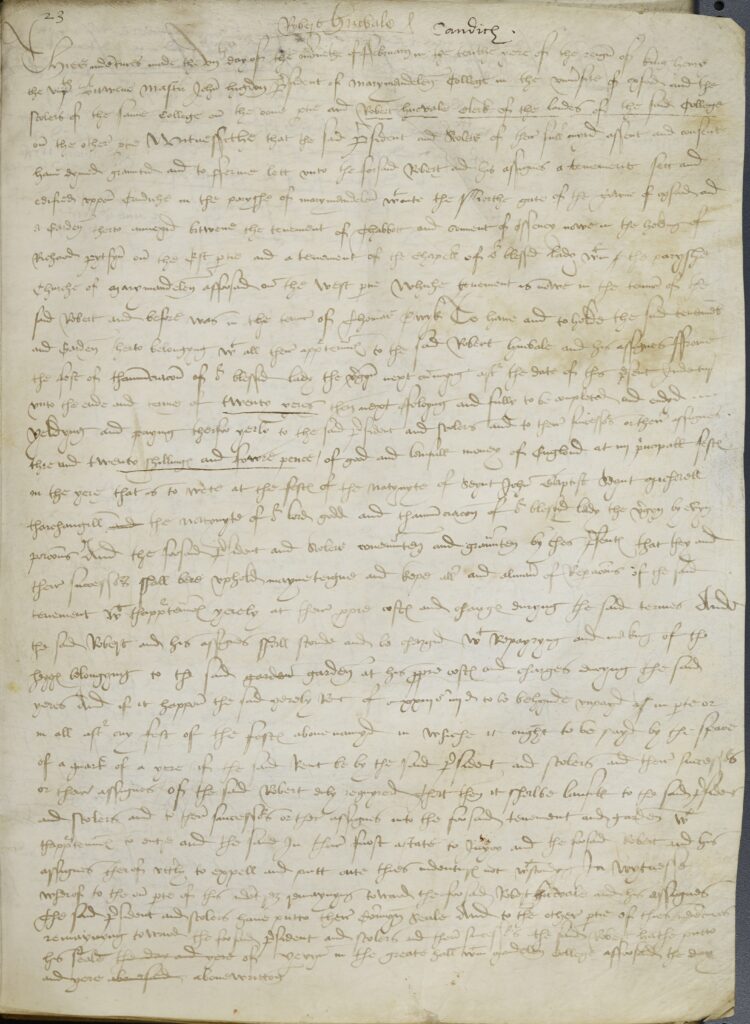

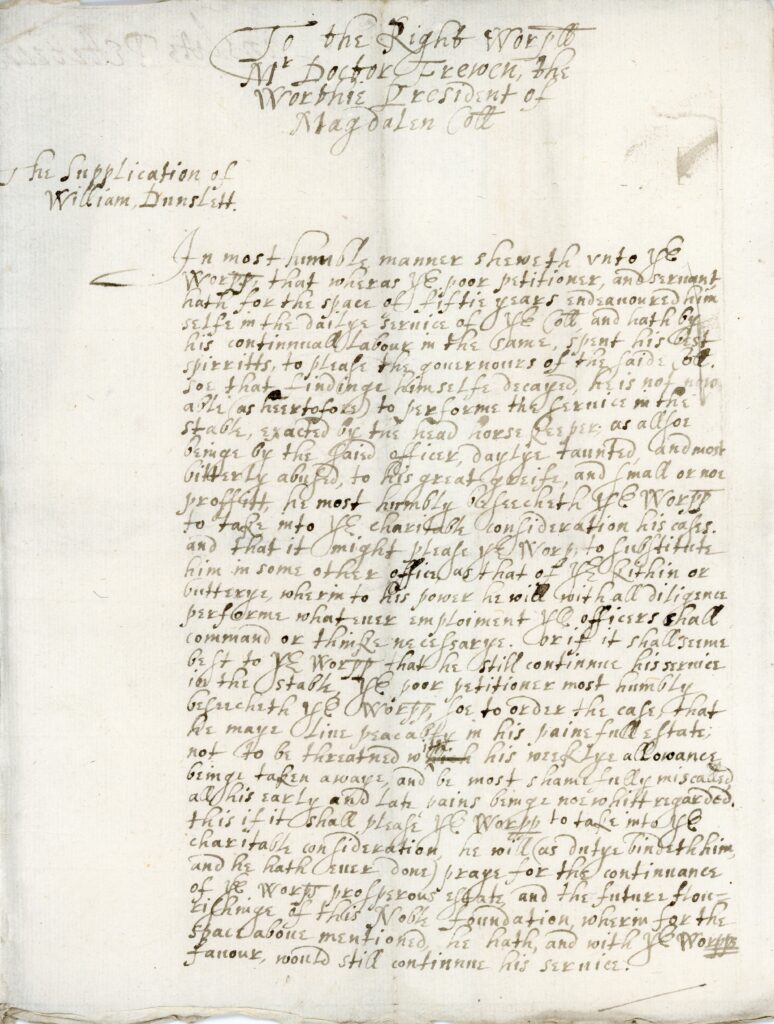

Petition

This petition is addressed to President Accepted Frewen (1626–44) by William Dunclett, who worked in Magdalen’s stables for fifty years. Having ‘spent his best spirits’ to please the college, Dunclett pleads for a transfer to the kitchen or buttery. Age and infirmity have begun to affect his capacity for stable work, on which account the head horse-keeper has ‘daily taunted’ him with the threat of withholding his weekly allowance.

Dunclett is almost certainly the husband of Mrs Dunclett, whose work to clean the library in 1628 is recorded elsewhere in this exhibition.

MCA, CS/35/4/3

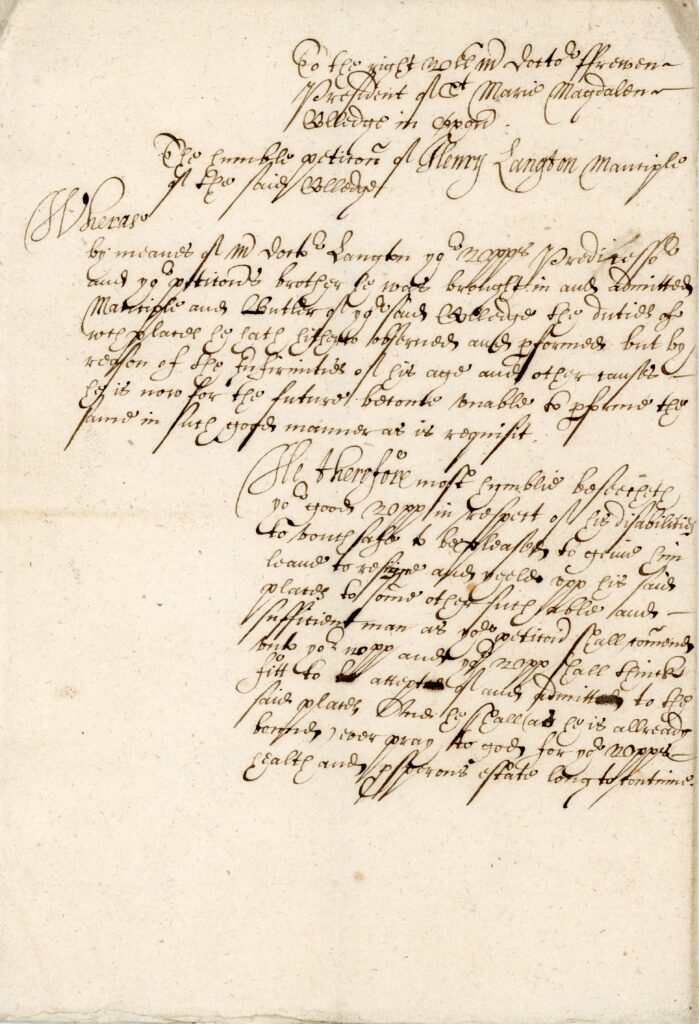

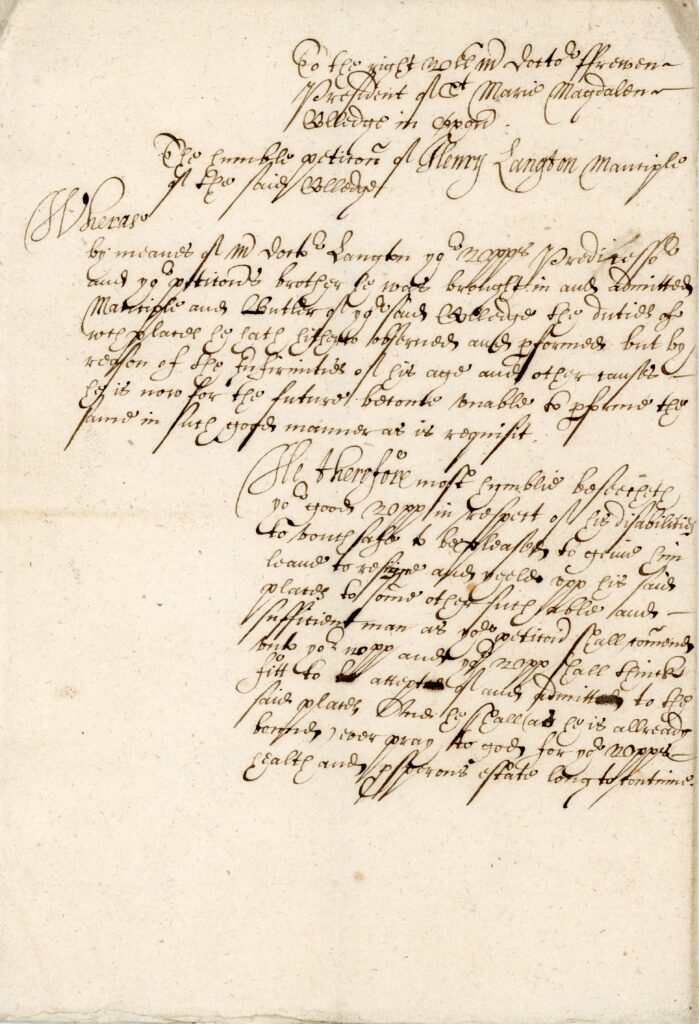

Retirement

Henry Langton was manciple of Magdalen in the early seventeenth century, a role that involved buying weekly provisions and supervising the distribution of bread and drink.

This document illustrates the college’s tendency to keep hiring decisions in the family. Henry Langton was brother to William Langton, a former Magdalen President (1610–26). Langton petitions his brother’s successor, Accepted Frewen (1626–44), for permission to resign owing to age-related disability. His replacement, he adds, should be an ‘able and sufficient man’ mutually approved by himself and Frewen.

MCA, CS/35/4/4

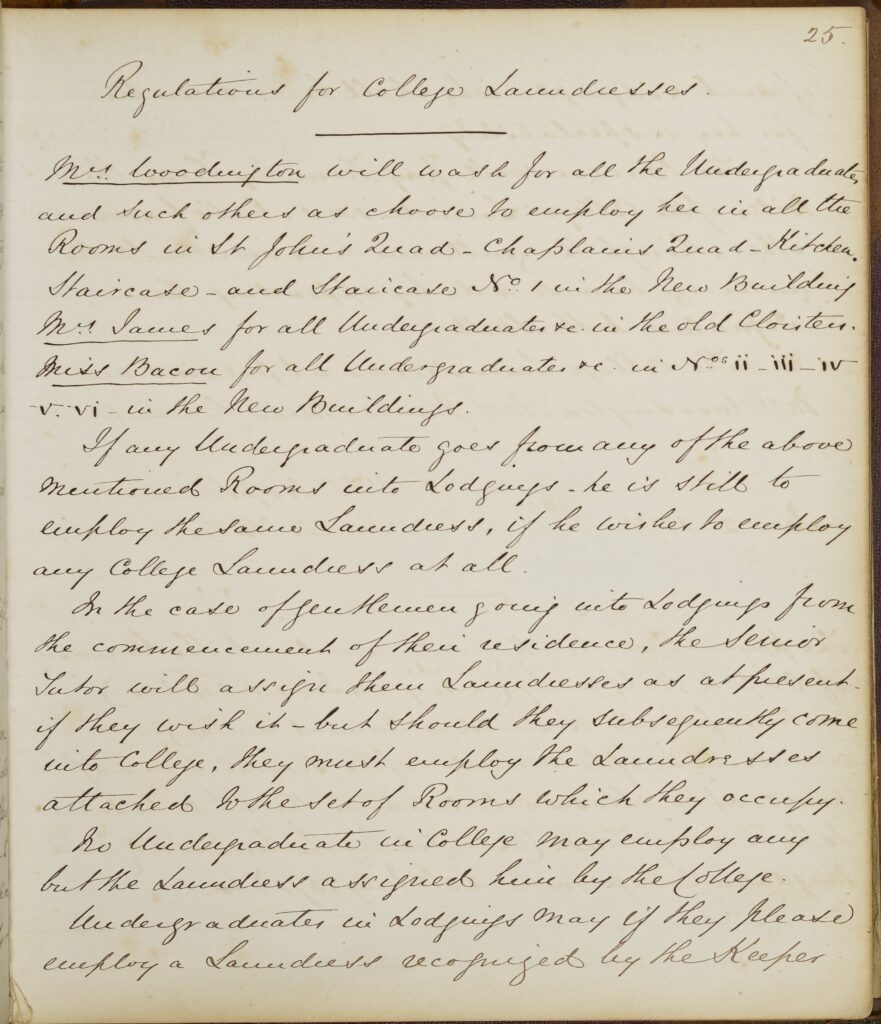

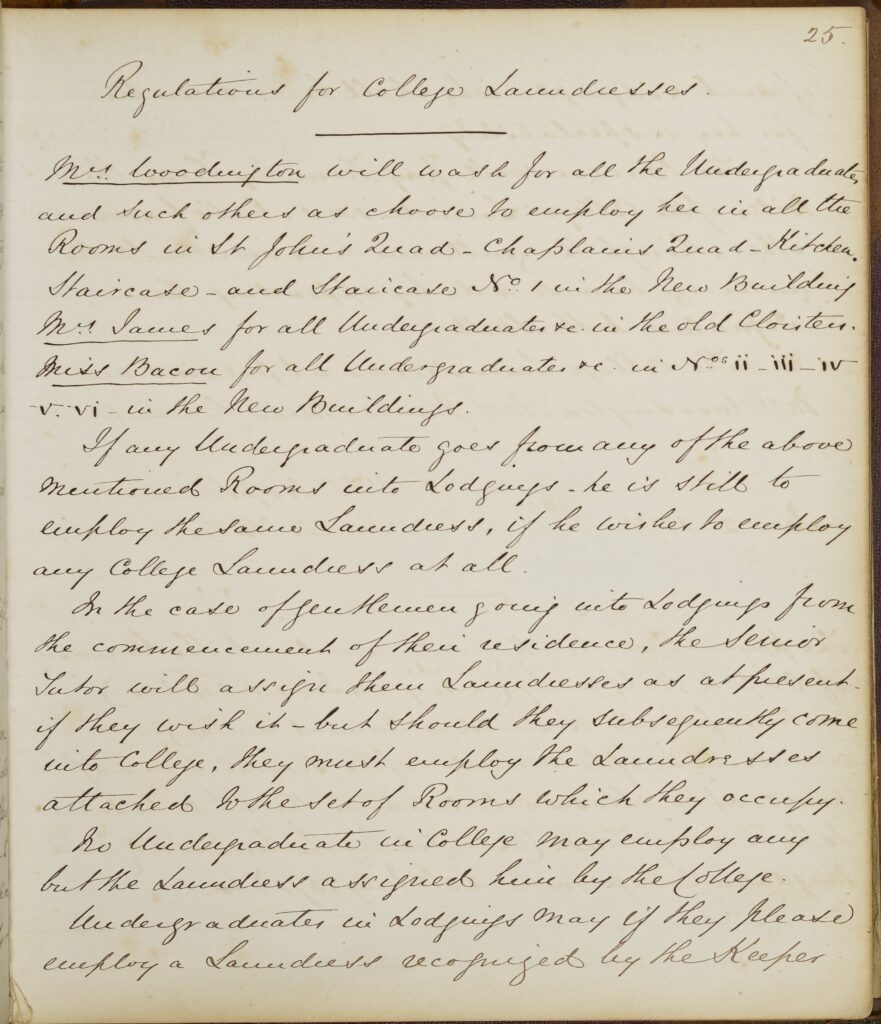

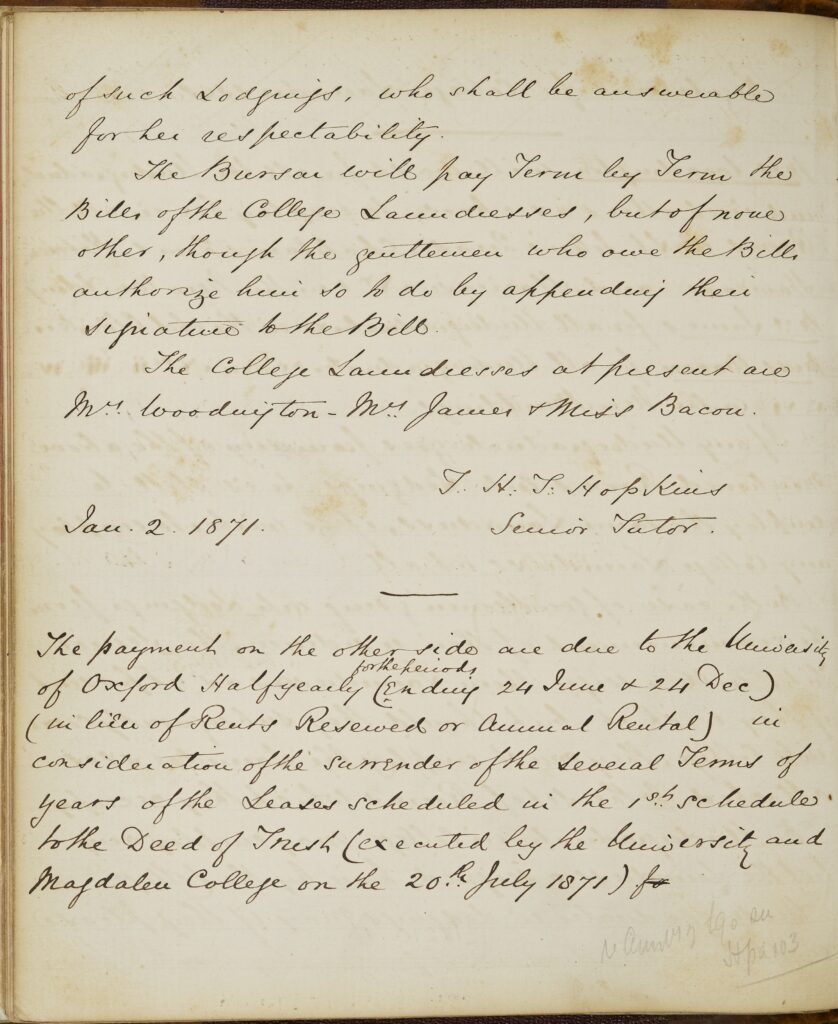

Regulations

Magdalen adhered to its original statutes, laid down by the Founder, until the middle of the nineteenth century. These included strict rules for the employment of servants, especially college laundresses.

Statute revisions were finally issued in 1857, but they make no mention of staff. The pages displayed here contain regulations from 1871 which stipulate that students are only to use the college laundresses, and only then those assigned to their rooms. It is unclear if these rules were laid down for financial reasons or as a nod to the moral qualms of the original statutes.

MCA, CP/2/63

Gardener

This photograph, which was taken by Roger Fenton (1819–69) at some point in the 1850s, shows Magdalen’s New Building from the south. Save the large sash blinds visible on some of the windows, and the row of trees running to the building’s west, this view is pretty much unchanged.

Standing in front of the building is a college gardener with his wheelbarrow, a sight that is still common today. The gardener’s identity is sadly unknown, but he is captured in what is potentially the oldest known surviving photograph of a member of Oxford college staff.

MCA, FA/1/11/3P/4